|

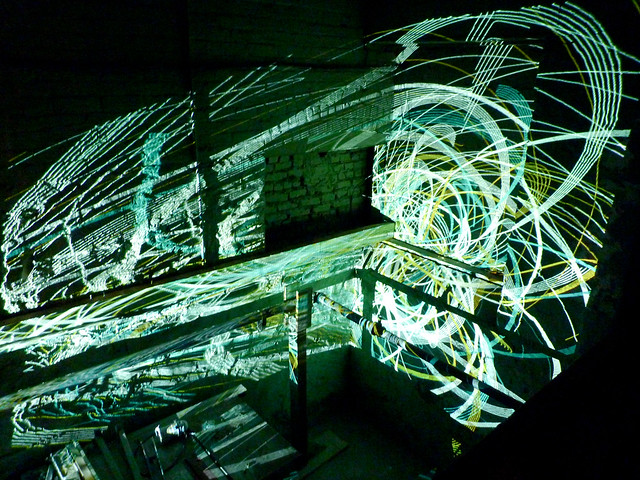

| Spectacular demollition of Ticosa. Photo by joernba |

Two years have passed since Ticosa was spectacularly demolished (27/1/2007), event acclaimed as the beginning of a new future for this area and for the city of Como (Italy) in general, after decades of urban stagnation and political incompetence of dealing with the massive building of a former silk factory closed in 1982 and used basically as parking. Ticosa, during 25 years of neglect, became a house for homeless, and an embarrassing symbol for the citizens, who saw in this big construction positioned facing one of the main streets of Como a shaming presence. So when bulldozers finally attacked the building, the ugliness, this was received as a great relief and as a big occasion to show that a new urban “era” was coming.

But why Ticosa was so problematic and ugly? And what if it was not ugly at all? This former factory appeared a big problem, something to get rid of, not because it was a bad building or it was lacking beauty (of course it was not built in greek marble), but because it reminded every day to people and politicians (even architects, why not?) their incapability to deal with a phenomenon typical of post-industrialization , and in general linked to the concept of the “shrinking cities”. I would say that the potential and the beauty of Ticosa was not understood, or discarded, thinking quite naively that the aura of shame that wrapped the building was definitively a single unity with its architecture. I propose some examples: the Olympiastadion in Berlin, built by the Nazis following the principles dictated by Albert Speer, concerning monumentality and the use of long-lasting materials, nowadays is still impressive, but it does not carry any nazi feeling; simply the building told to the ideas that inspired its design and construction to fuck off. P. P. Pasolini, talking about the city of Sabaudia was illuminating in this sense. Or many residential projects started with the best proposals (Gropiusstadt in Berlin, Zen in Palermo by Vittorio Gregotti just to name a couple) turned out as terrible places to live in, because the development of architecture follows many tracks at the same time (social, political, economical) and the designer can be the one who starts a process, but cannot control it since the very moment it starts. Then time becomes the leading factor. In this view, what can seem ugly for us, could suit other incoming generations, and if for Gertrude Stein “A rose is a rose is a rose”, an idea or a feeling are not a building, which is capable of changing meaning in response to the kind of society it is surrounded by.

Ticosa was therefor extremely beautiful, a real piece of industrial archaeology, that, instead of being pulled down, regaining density of use (as a cultural centre, apartments, a discotheque...) could have stand proudly the near facade of St. Abbondio medieval church and be a proof of the multiple lives of architecture.

Anyhow another option could also have been possible, interesting as well: following John Ruskin’s theory about ruins, one can let time run over a building, permitting a controlled decay, just not touching it (and avoiding also vandalism), creating in this way a true industrial ruin, a fertile ground for imagination, architecture of the desire, as a “dark” and intriguing opposition to “nice architecture”, conveying the feeling of risk, a concept that disappeared almost entirely in architectural theory, apart for a few people, like Francois Roche. Von Sacher-Masoch would say: “pain is part of the pleasure.”